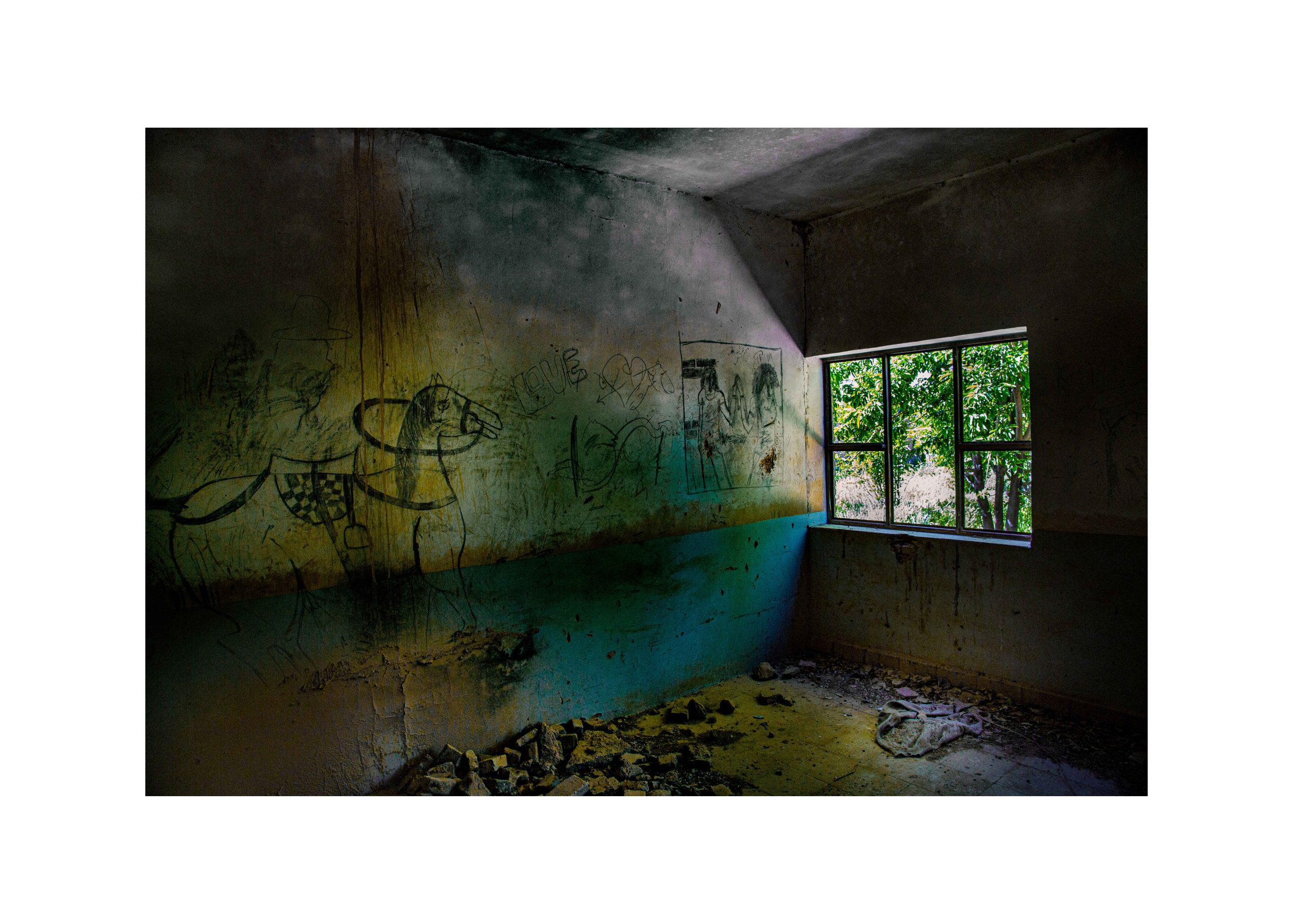

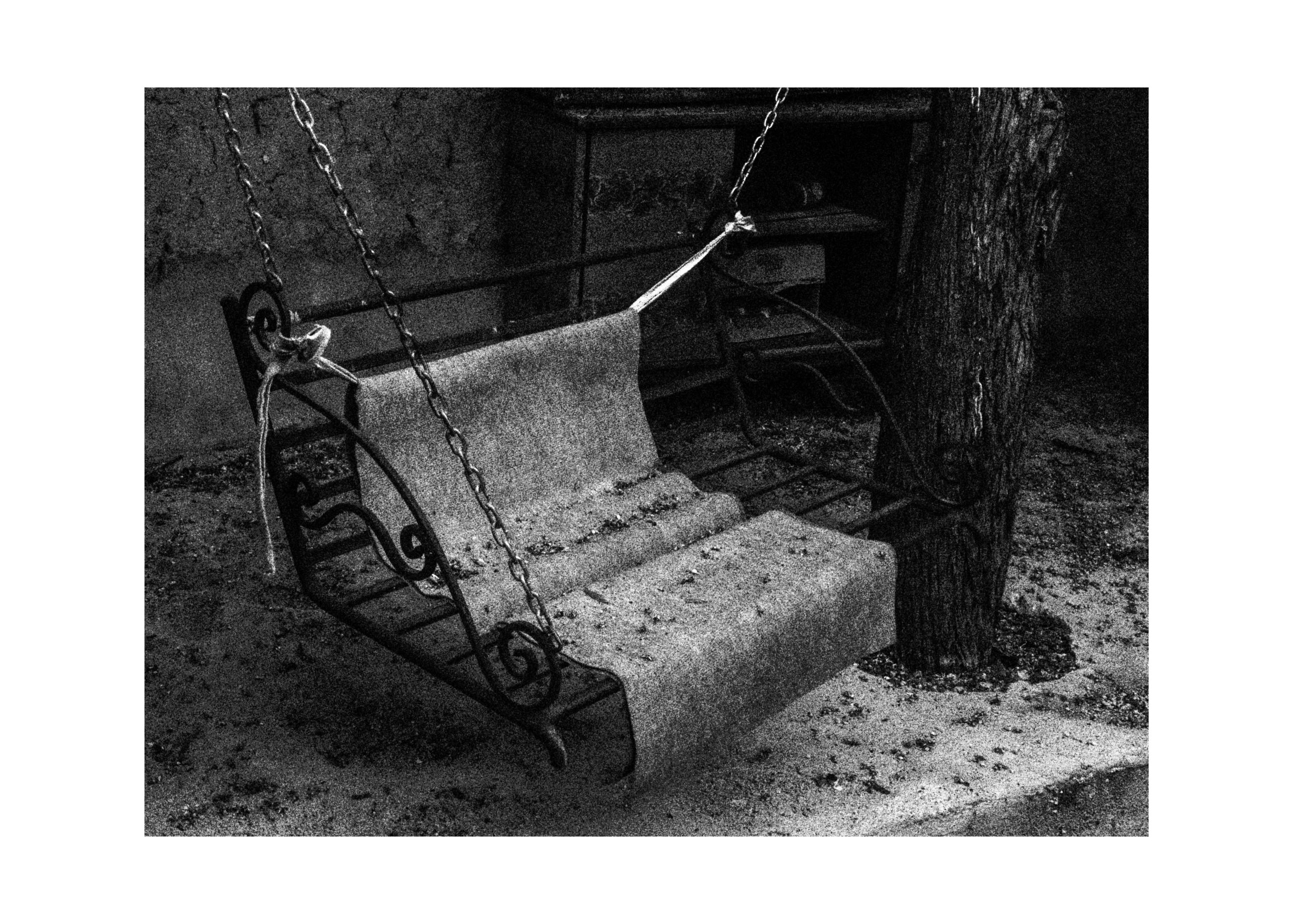

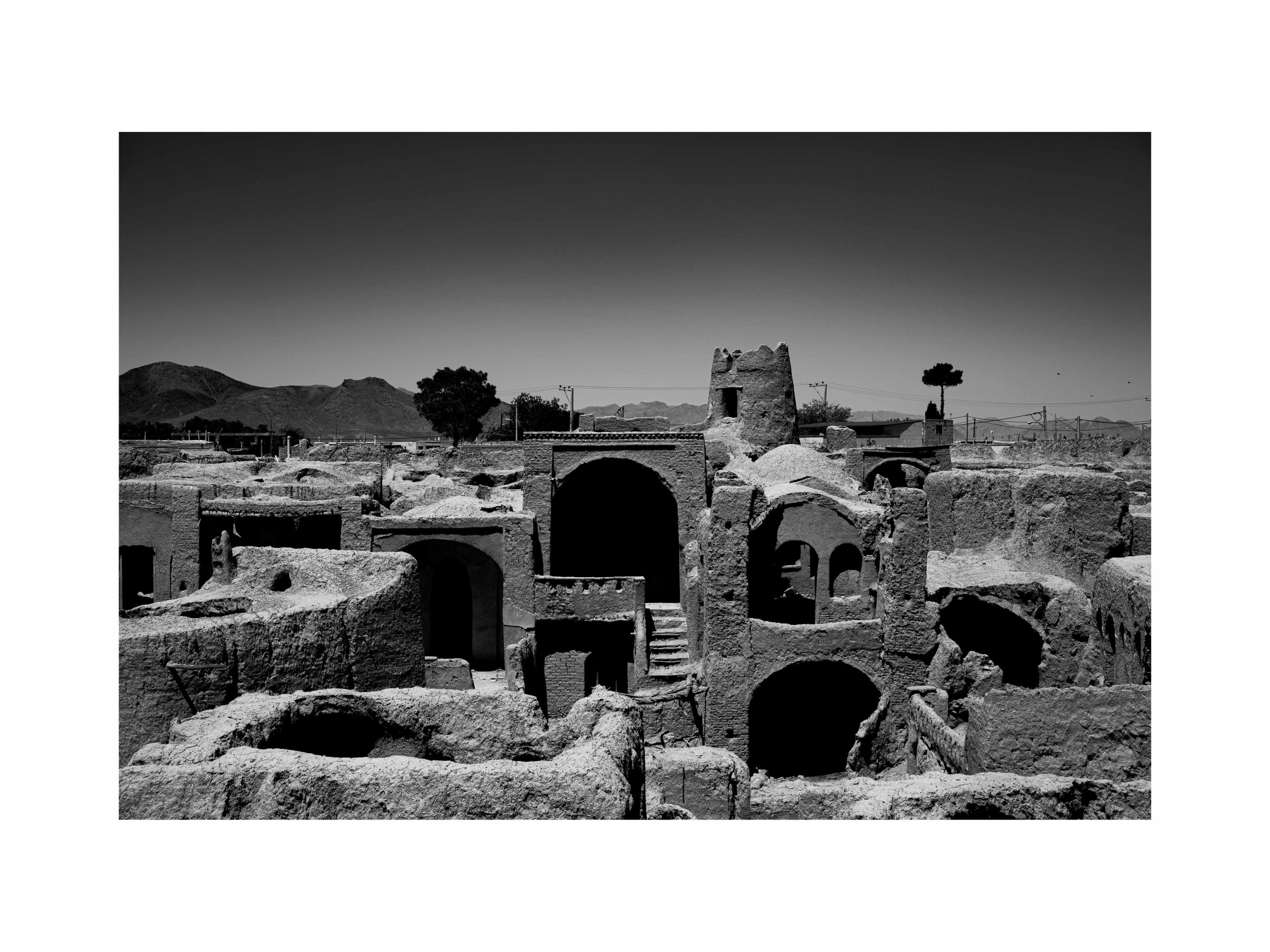

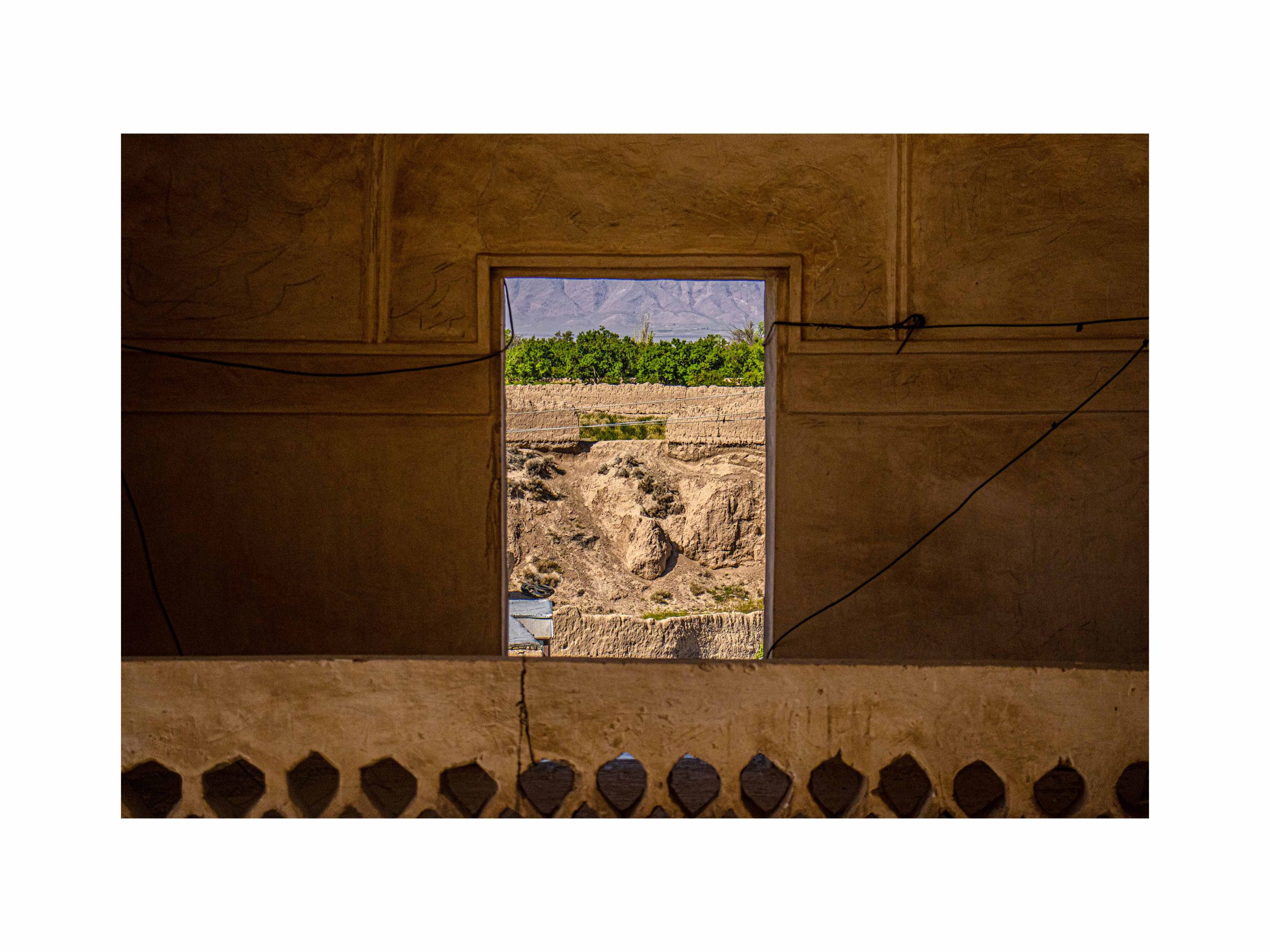

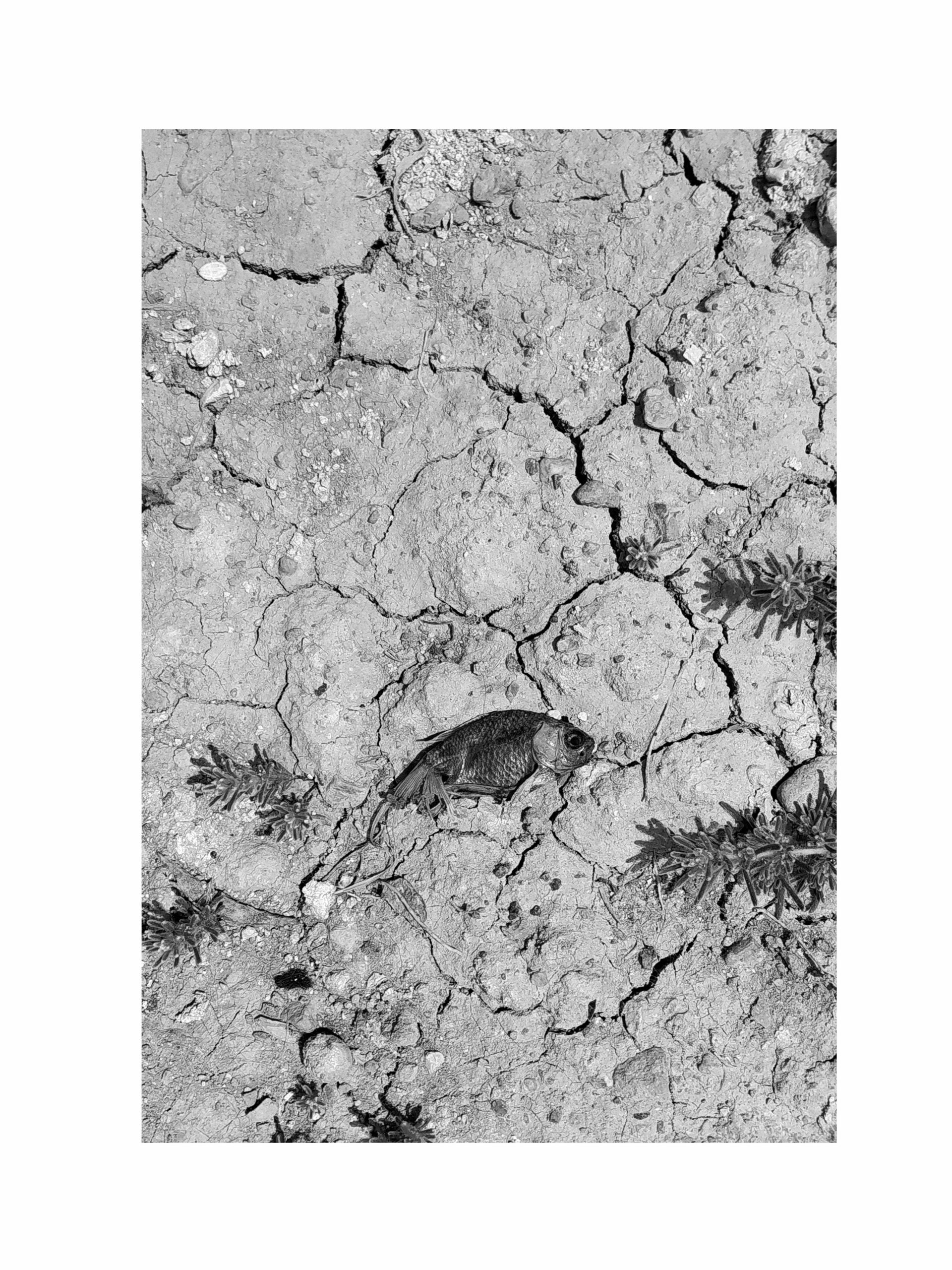

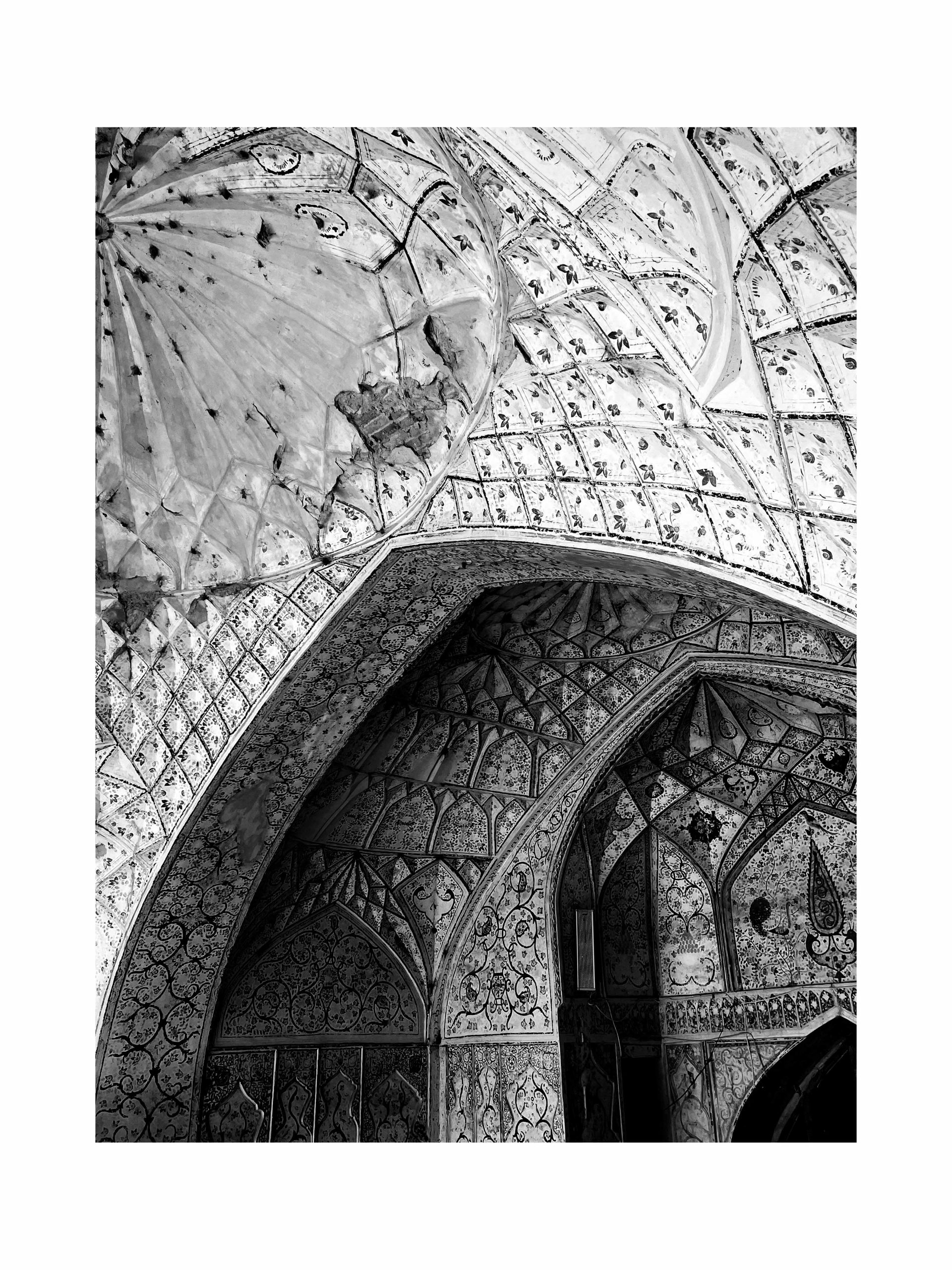

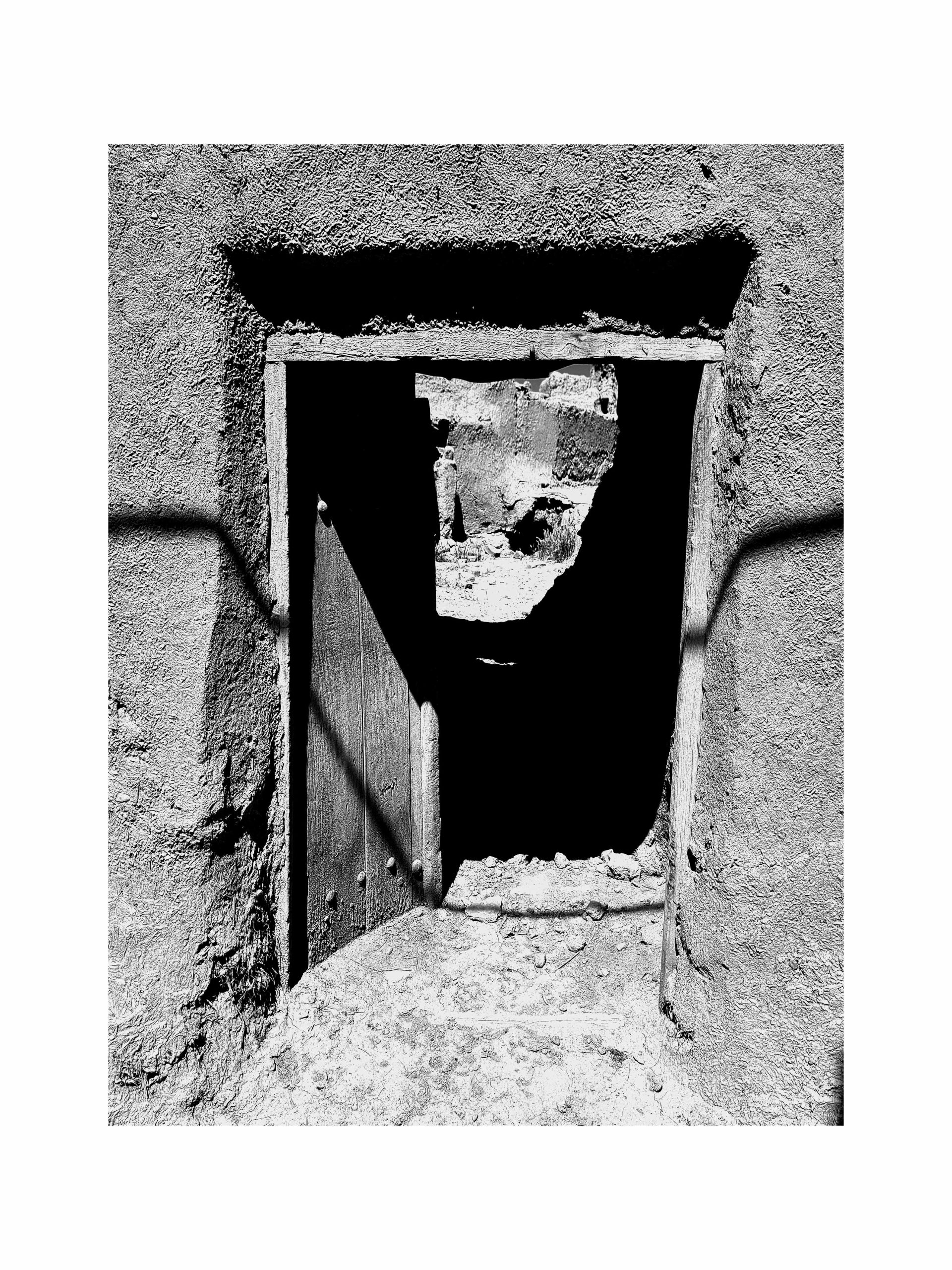

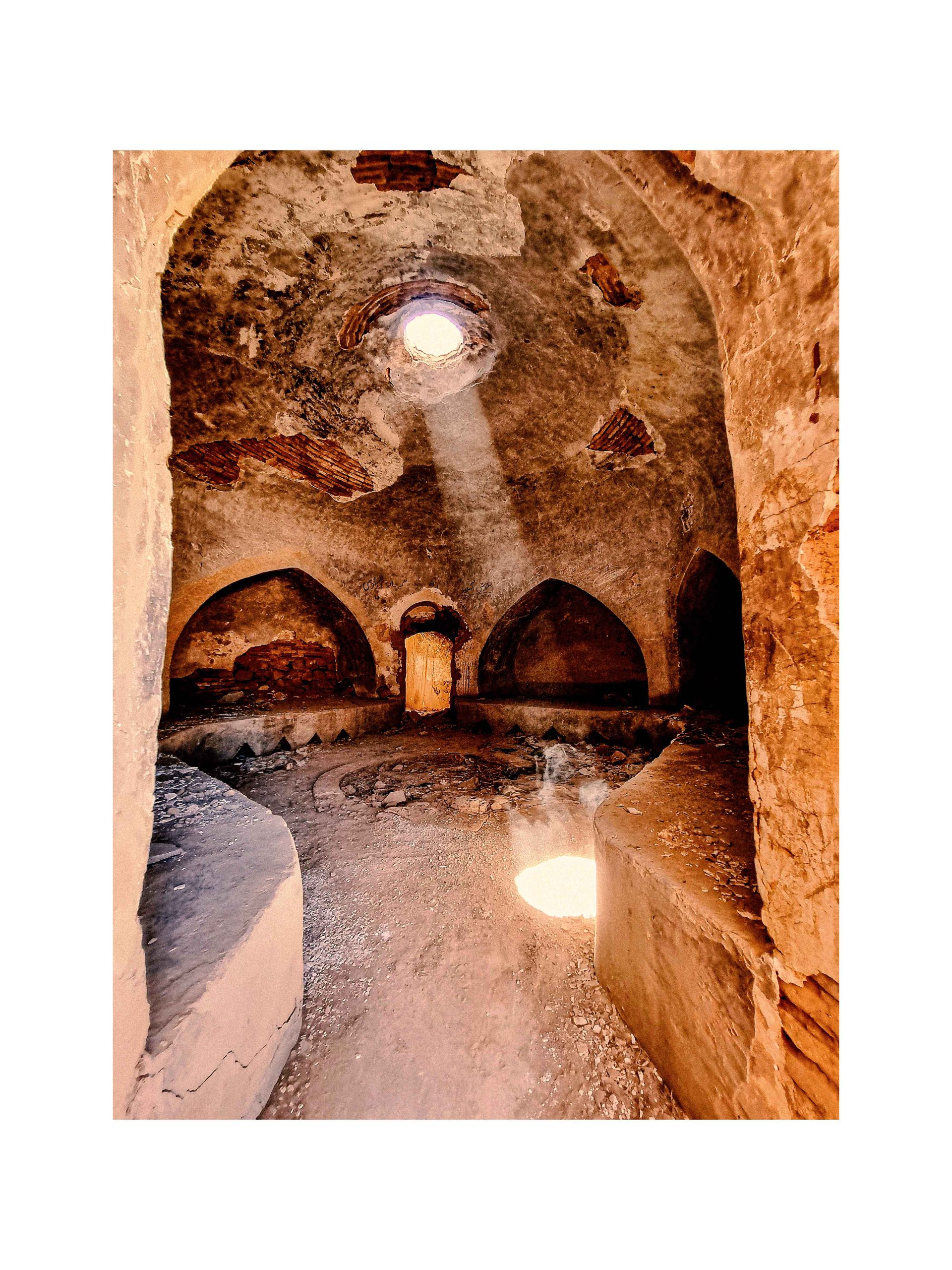

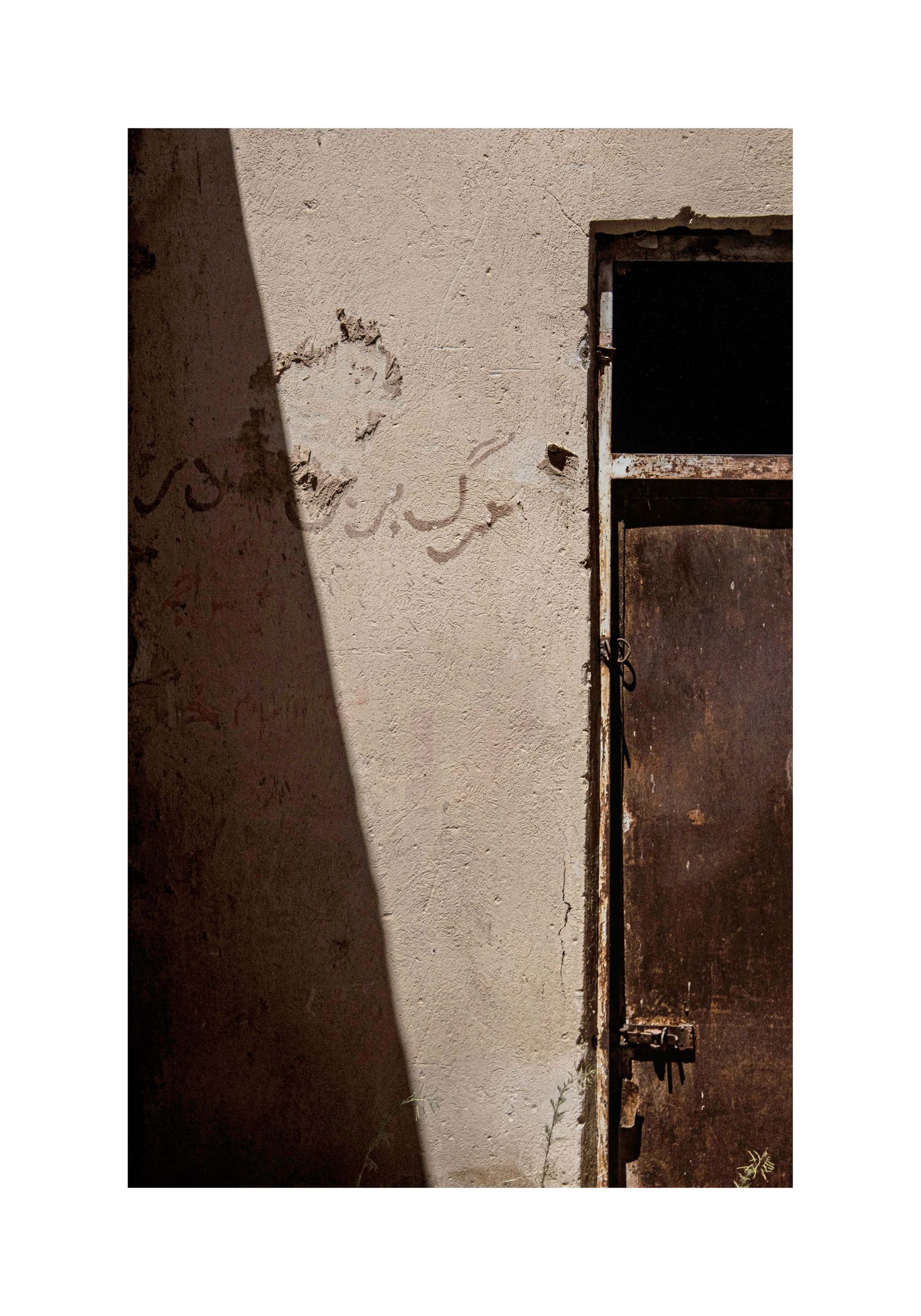

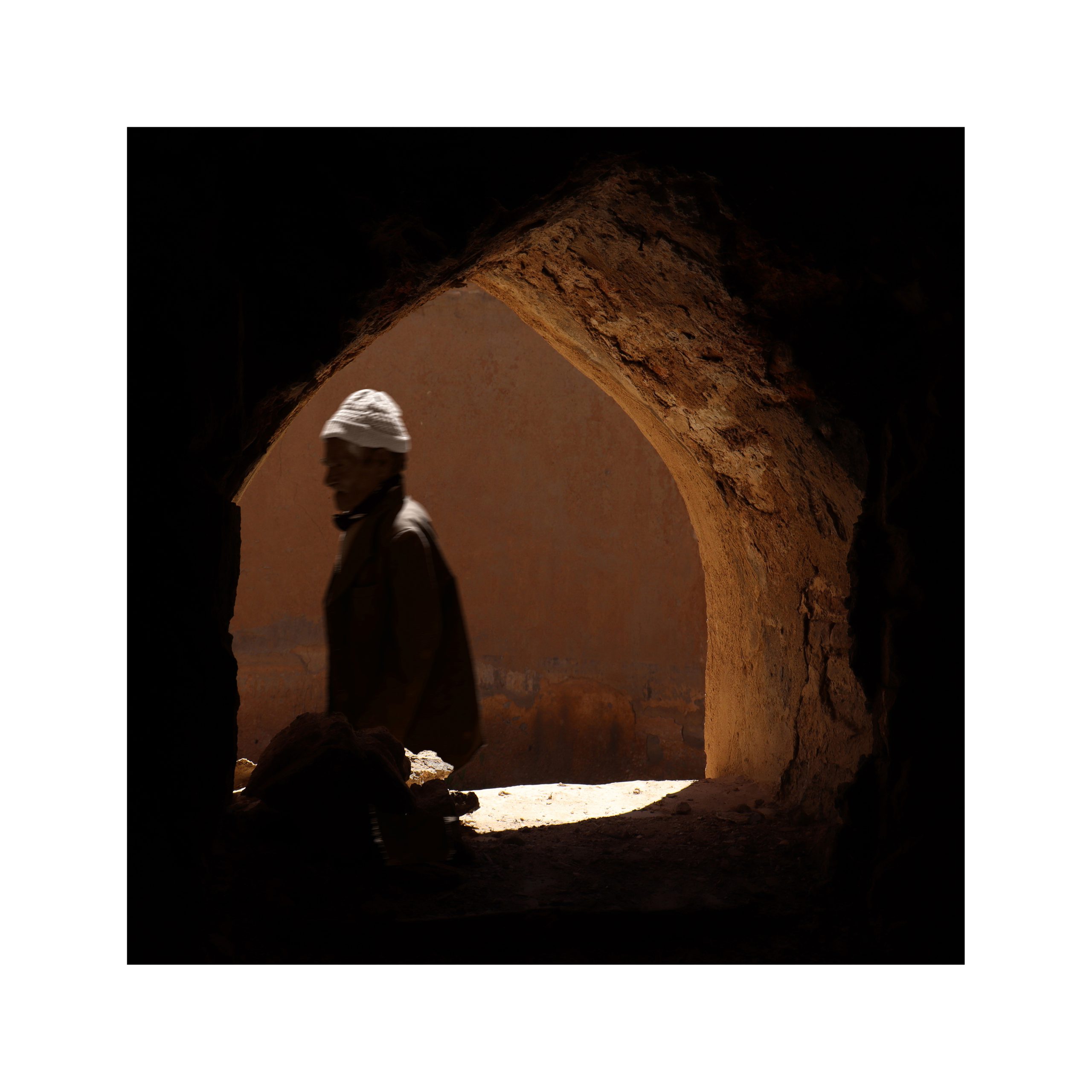

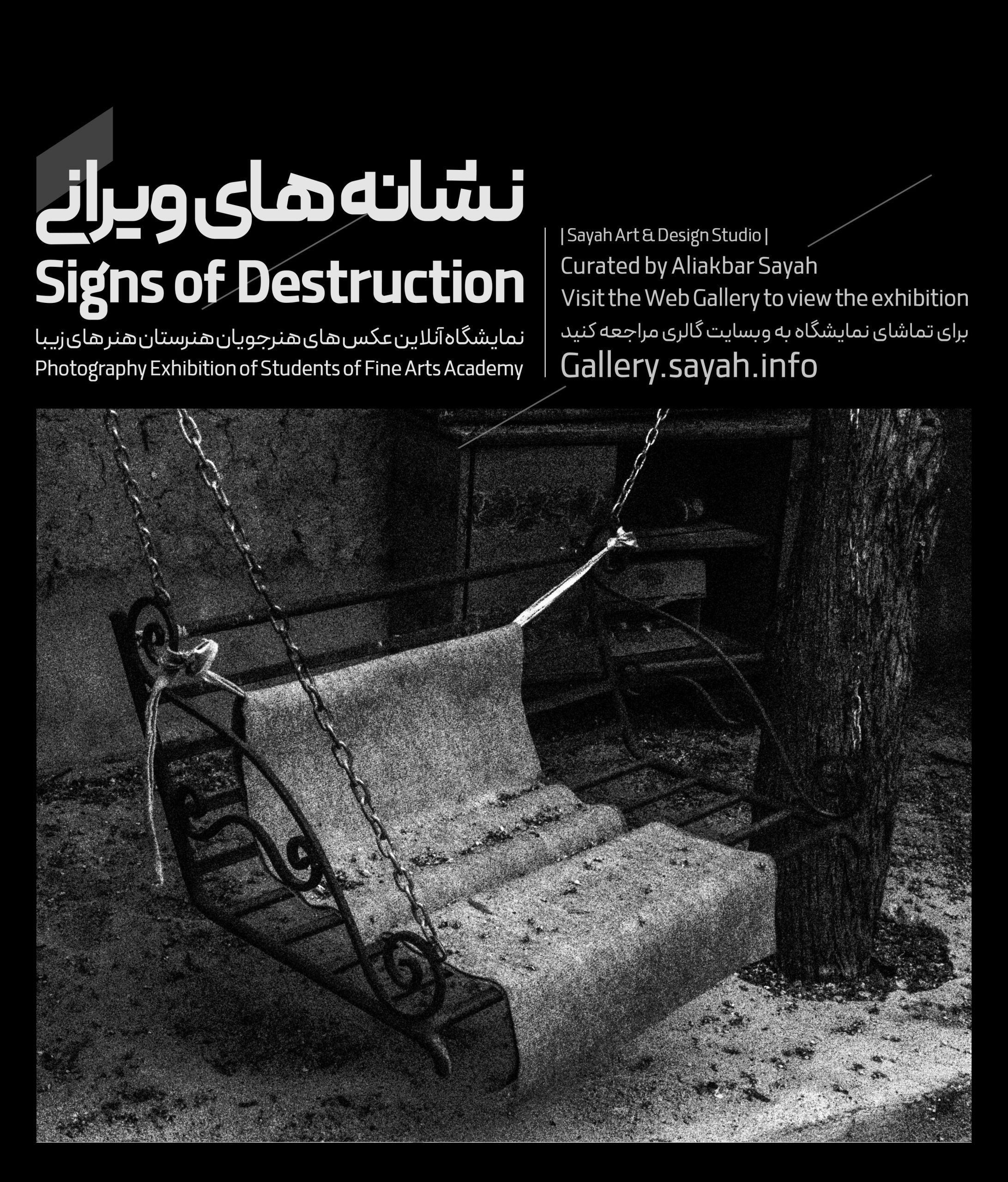

It is a collection of photos of the graphic arts students of the Academy of Fine Arts. The criterion for selecting these works was beyond observing the basics and principles of art (composition) and we prioritized meaning over photographic aesthetics. The main idea started from Lee Fried Lander's photos, under the title "Letters from People". The goal was to find the legacy of today's people for future generations, and they will inherit nothing but our ruins. Every photo is a sign of the spirit of the people who learned to destroy everything they have for their own living.

These are not just images of destruction, but a warning for our historical performance.

نشانه های ویرانی، مجموعه عکس هایی از هنرجویان گرافیک هنرستان هنرهای زیباست که معیار انتخاب این آثار، فراتر از رعایت مبانی و اصول هنری (کمپوزیسون) بود و ما معنا را بر زیبایی شناسی عکاسانه اولویت قرار دادیم. ایده ی اصلی از عکس های لی فرید لندر، تحت عنوان “نامه هایی از مردم” آغاز شد. غایت، یافتن میراث مردمان امروز برای آیندگان بود و آنها وارث هیچ چیز نخواهند بود جز ویرانی های ما. هر عکس نشانه ایست از روح زمانه ی مردمانی که آموختند برای زیست خود دست به نابودی هرچه دارند بزند.

اینها نه تصاویری صرف از ویرانی ها، بلکه هشداری برای عملکرد تاریخی ماست.

Amir Abbas Asadi | Abolfazl Heydarpour | Mohammad Matin Javadi | Mohammad Reza Rasti | Mohammad Matin Rahmati | Mehdi Sarvari | Mohammad Saleh Kaviani | Sadegh Ghavami | Amir Mohammad Alizad | Moein Naderi | Yousef Manochehri | Mehdi Mosavi

امیر عباس اسدی | ابوالفضل حیدرپور | محمد متین جوادی | محمد رضا راستی | محمد متین رحمتی | مهدی سروری | محمد صالح کاویانی | صادق قوامی | امیر محمد علیزاد | معین نادری | یوسف منوچهری | سید مهدی موسوی

The Motives behind the Destruction of Cultural Heritage

Destruction of architecture and art objects is an ancient practice. From Troy and Tenochtitlan to Dresden and Munich and on to Bamiyan and Palmyra today, the obliteration of historic cities and heritage sites has taken place throughout history and across cultures. In the West, such events as the Protestant Reformation led to the destruction of many churches and religious furnishings. Later, massive aerial bombing was the major cause of cultural heritage destruction. During WWII, aerial attacks destroyed a substantial portion of Europe’s historically significant buildings and museums. In Germany alone, not only major architectural monuments, but also entire cities, most famously Dresden after its firebombing in February of 1945, were obliterated.

Yet, not all destructions stem from ignorance, ideological stances, or a shortage of resources, financial or otherwise. In truth, many progressive and modernist views have negatively affected the cultural heritage of the Middle East. Colonial urban renewal—for example, the destruction of Algiers’ historic core in the early years of French occupation—counts as destruction, as do the urban renewal schemes of the 1950s and 1960s that were carried out by newly independent governments with the help of European architects and planners.ndeed, the creation of many nation-states coincided with a simultaneous celebration of some monuments and a deliberate obliteration of others. As Talinn Grigor reveals, when Reza Pahlavi became Shah of Iran in 1925, he destroyed many iconic monuments built by the previous Qajar dynasty. Likewise, during the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Reza Shah’s own tomb tower was the first monument to be brought down by a group of hardcore revolutionaries guided by the notorious Ayatollah Mohammed Sadeq Khalkhali, the hardline cleric and judge of the revolutionary courts.

or lesser-known areas. Equally essential are ordinary built environments that are meaningful to people on the ground rather than to the international community and world heritage organizations. The more modern and insignificant the damaged buildings—or, what historian Nick Yablon calls “untimely ruins”—the better reminders of the sufferings of their occupants. Thus we must ensure that several damaged buildings are kept as such to denote the pain of their human occupants for generations to come. These “untimely ruins” will stand as chief reminders, because as environmental historian Rebecca Solnit asserts, “[m]emory is always incomplete, always imperfect, always falling into ruin; but the ruins themselves … are … our links to what came before, our guide to situating ourselves in a landscape of time.” And hopefully these ruins will not be perceived as mere sites of grief, but of far-reaching promises, hence forging a new revolutionary future, to borrow from Walter Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Finally, it is hoped that more novel avenues of inquiry are opened for historians to study the destructions in systematic and theoretically stimulating ways. Indeed, this collection aspires to bolster the emerging body of literature that is enriching our understanding of the many motives behind the destruction of Middle Eastern architecture and its cultural heritage and ways to counter them.