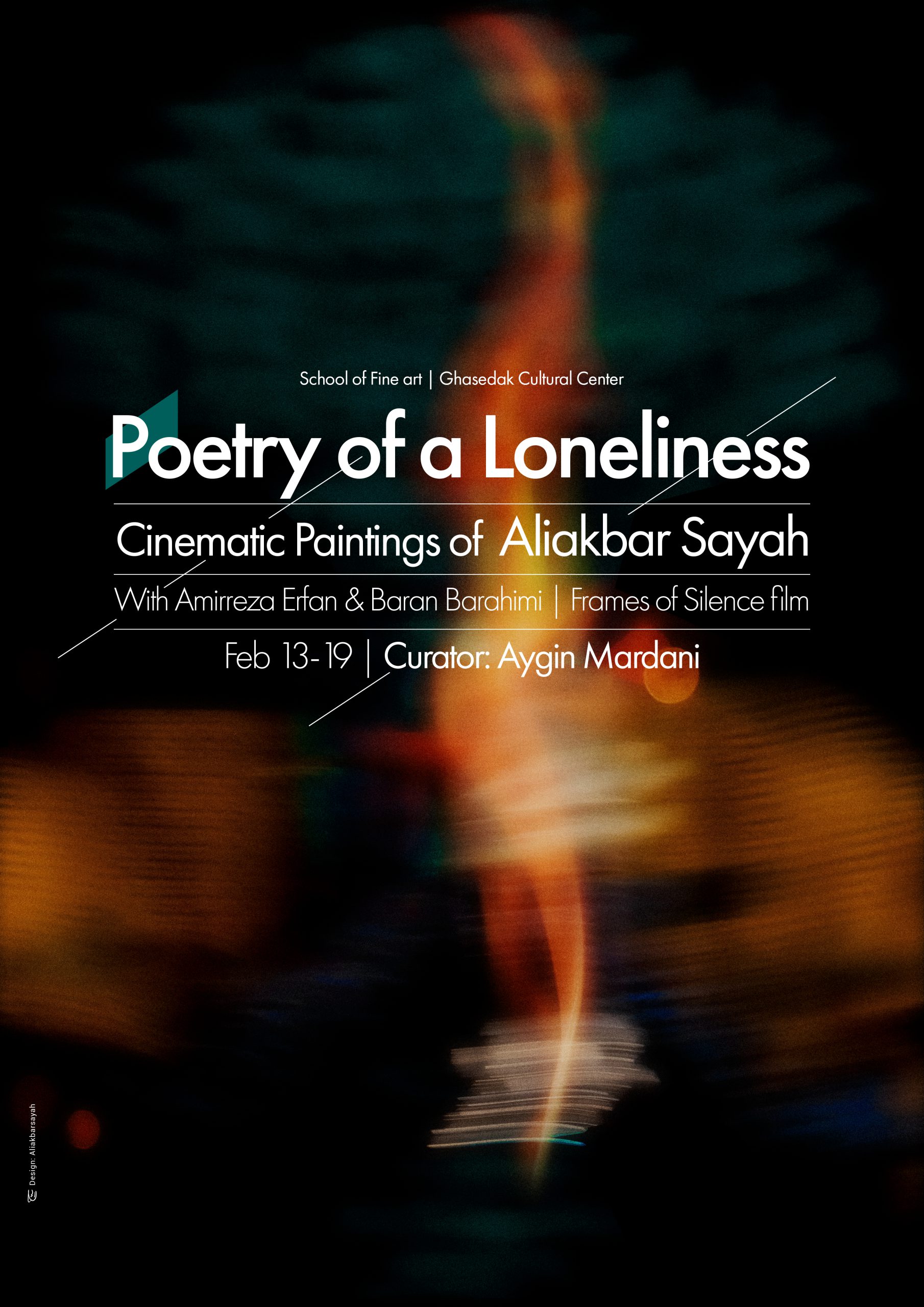

Cinematic Painting by Aliakbar Sayah | نقاشی های سینمایی علی اکبرسیاح

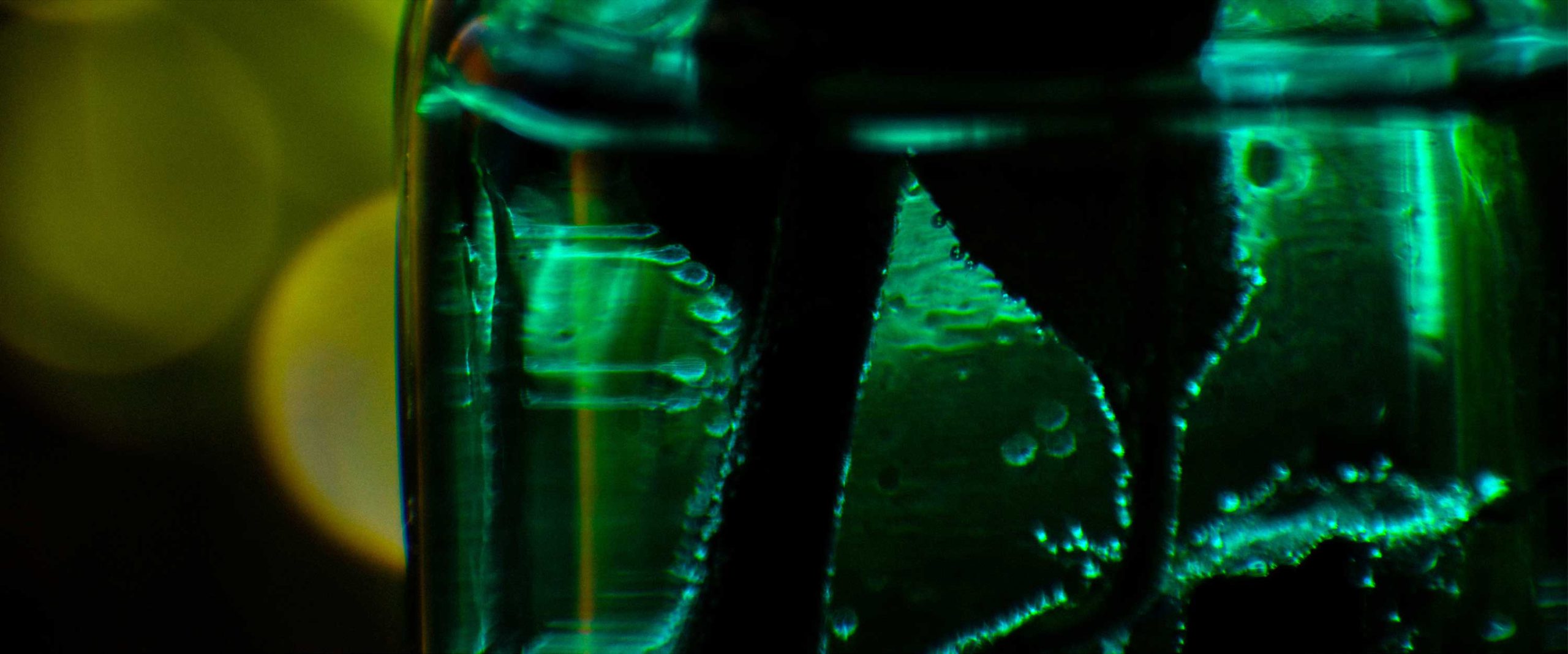

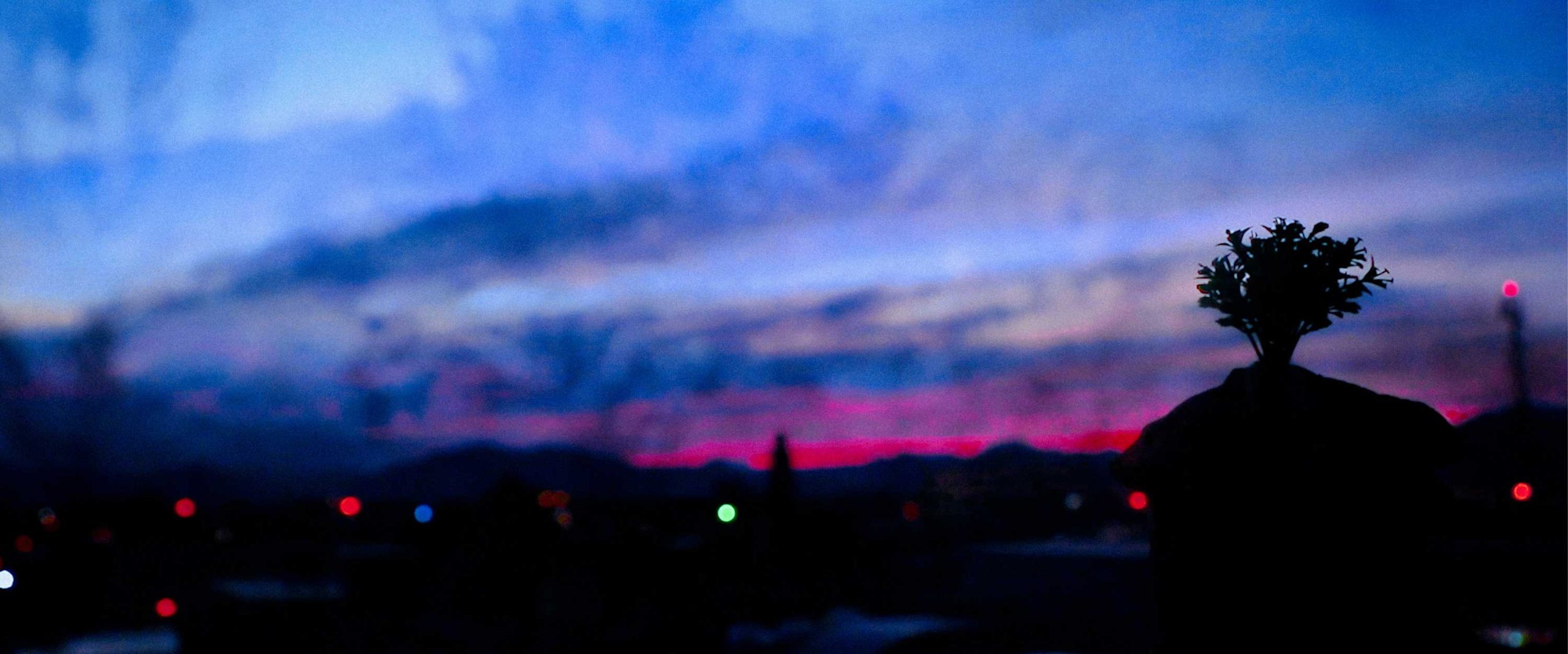

The exhibition " Poetry of a loneliness " is clips from the short film "Dweller of Silence" by Aliakbar Sayah. The selected frames, by calling the viewer's mind to extend and receive the works dramatically, look for a kind of rebellion and rebellion against the characteristics of painting and two-dimensional images, and at the same time, maintain the nature of breaking away from and maintaining a distance from the external reality. Is. The images seem to compel the viewer's mind to expand and unframe, and to remain within the fence of the frames

. This unfinished debate between painting and cinematographic features in the framing of photos has led to the creation of the concept of "cinematic painting" by the artist. Among the remarkable connections of the selected photos with the painting space are their lighting characteristics. The use of light and shadow in the structure of a visual work is not only limited to lighting and physical characteristics of light, its effect on the color and structure of the formalism of objects, but it is very effective in creating harmony, balance and rhythm in composition. The lighting space in the presented photos is reminiscent of baroque paintings.

By using the physics of light and paying attention to its mystical and sublime meaning, baroque painters achieved suitable and remarkable compositions with the content of their works.Ali Akbar Sayah has used the emotional and expressive ability of lighting to bring the relationship created by light between face and content in baroque painting into his cinema and approach the world of painting, and in this way, the dreamlikeness of "poetry". paint the inevitable reality of "loneliness" and make it easier to stay and live in "yourself"...

شاعرانگی یک تنهایی، برش هایی از فیلم کوتاه ساکن سراي سکوت اثر علی اکبر سیاح است. قابهاي انتخاب شده، با فراخواندن ذهن بیننده به سوي امتداد یافتن و دریافت دراماتیک از آثار، به دنبال نوعی سرکشی و طغیان در برابر ویژگی هاي نقاشی و تصویر دو بعدي است و در عین حال سرشت گسستن از و حفظ فاصله با واقعیت بیرونی را حفظ کرده است. تصاویر گویی ذهن بیننده را هم وادار به گسترش و قاب زدایی و هم ملزم به ماندن در حصار قابها میکند. این جدال ناتمام میان ویژگی هاي نقاشانه و سینمایی در قاب بندي عکسها، منجر به برساختن مفهوم »نقاشی سینمایی« توسط هنرمند گردیده است. از جمله اتصالات قابل توجه عکسهاي برگزیده، با فضاي نقاشانه، ویژگی هاي نورپردازي آنهاست. کاربرد نور و سایه در ساختار یک اثر تجسمی تنها به نورپردازي و خصوصیات فیزیک نور، تأثیر آن بر رنگ و ساختار فرمالیسم اشیا خلاصه نمی شود بلکه کاربرد بسیار موثري در ایجاد هماهنگی، تعادل و ریتم در ترکیب بندي دارد. فضاي نورپردازي در عکسهاي ارائه شده، یادآور نقاشی هاي باروك است. نقاشان باروك با استفاده از فیزیک نور و توجه به معناي عرفانی و متعالی آن به ترکیب-بندي هایی مناسب و قابل توجه با محتواي آثارشان دست یافتند. علی اکبر سیاح، قابلیت عاطفی و بیانگرانه نورپردازي را به کار بسته است تا رابطه ایجاد شده توسط نور میان صورت و محتوا در نقاشی باروکی را در سینماي خود وارد نموده و به دنیاي نقاشی نزدیک شود و از این طریق، رویاگونه بودن شاعرانگی، به واقعیت گریزناپذیر تنهایی رنگ بپاشد و ماندن و زیستن در خود را هموار کند ...

Curated by Aygin Mardani | کیوریتور دکتر آیگین مردانی

Filmmaker,Curator, Art Director and Puppet Artist

Aliakbarsayah Born in 2000, Iran / Founder of Sayah Art & Design Studio / Bachelor of Animation Filmmaking, School of Fine art / Instructor of cinema Lighting /Art Director of Ghasedak Cultural Center / Designer and Art Director of Phoenix / Instructor of Animation and Photography at School of Fine art.

Aliakbarsayah’s exhibitions are a display of interdisciplinary works between cinema and visual arts such as painting and cinema. In all of them, loneliness and fantasy are two inseparable elements that become motifs and become the main motif. Aliakbarsayah, In her frames, the tourist is always making references, different references to old films and paintings and even references to herself. He use objects as symbols to represent the innermost being of a person and an inner journey. A journey from the outside to the inside, which is symbolized by objects such as dolls and glass vases.

Aliakbarsayah, These frames tell a story, but each of the words of the poem are put together and form the poetic. Painting and lighting are also facilities that Sayah use to get closer to their main sources, cinema and painting, and to add to their poetry. In fact, Aliakbarsayah see the cinema camera as a canvas and paints in the medium of film and experiences the cinema in her collection of photographs.

A part of The Cinema of Poetry

The article by Pie Paolo Pasolini

whereas the instruments of poetic or philosophical communication are already extremely perfected, truly form a historically complex system which has reached its maturity, those of the visual communication which is at the basis of cinematic language are altogether brute, instinctive. Indeed, gestures, the surrounding reality, as much as dreams and the mechanisms of memory, are of a virtually pre-human order, or at least at the limit of humanity in any case pre-grammatical and even premorphological (dreams are unconscious phenomena, as are mnemonic mechanisms; the gesture is an altogether elementary sign, etc.).

The linguistic instrument on which cinema is founded is thus of an irrational type. This explains the profoundly oniric nature of cinema, as also its absolutely and inevitably concrete nature, let us say its objective status.

Every language is recorded in a dictionary, incomplete but perfect, of the sign-system of his surroundings and of his country. The work of the writer consists in taking, from this dictionary, words, like objects arranged in a drawer, and in making a particular use of them particular insofar as it is a function both of the writer’s historical situation and of the history of these words. The result is an increase of historicity for the word, that is a growth of meaning. If this writer passes into posterity, his “particular use of the word” will figure in future dictionaries, as another possible use of the word.

The expression, the invention of the writer adds, thus, to the historicity, that is to the reality, of the language: he makes use of the language and serves it both as a linguistic system and as a cultural

tradition. But this act, toponymically described, is one: it is a new elaboration of the meaning of a sign which was found classified in the dictionary, ready for use.

In return, the act of the filmmaker, although fundamentally similar, is nonetheless much more complex.

A dictionary of images does not exist. There are no images classified and ready for use. If by chance we wanted to imagine a dictionary of images, we would have to imagine an infinite dictionary, just as the dictionary of possible words remains infinite.

The cinema author has no dictionary but infinite possibilities. He does not take his signs, his im- signs, from some drawer or from some bag, but from chaos, where an automatic or oniric communication is only found in the state of possibility, of shadow. Thus, toponymically described, the act of the filmmaker is not one but double. He must first draw the im-sign from chaos, make it possible and consider it as classified in a dictionary of im-signs (gestures, environment, dreams, memory); he must then accomplish the very work of the writer, that is, enrich this purely morphological im-sign with his personal expression. While the writer’s work is esthetic invention, that of the filmmaker is first linguistic invention, then esthetic.

It is true that after some fifty years of cinema,, a sort of cinematic dictionary has been established, or rather a convention, which has this curiosity it is stylistic before being grammatical.

Let us take the image of train wheels rolling amid clouds of steam. This is not a syntagma, but a styleme. [Styleme = a unit of style. Tr.] This allows us to suppose that, from all evidence, cinema will never attain a true grammatical normativity which would be proper to it, but rather, so to speak, a stylistic grammar each time a filmmaker makes a film, he has to repeat the double operation of which I spoke and, as a rule, be content with a certain quantity of uncounted means of expression, which, born as stylemes, have become syntagmas.

The meaning of words fits the evolution which presides over the creative fashion of clothes or of the lines of cars. Objects, in return, are impenetrable to it: they do not allow modification and say by themselves only what they are at that moment. The imaginary dictionary in which the filmmaker classifies them in the course of the primary stage of his work is not sufficient to give them a historical background, significant for all, now and forever. One thus notes a certain determinism in the object which becomes a cinematic image. It is natural that this should be so, for the word (linguistic sign) used by the writer is rich with a whole cultural, popular and grammatical history, whereas the filmmaker who is using an im- sign has just isolated it, at that very moment, from the mute chaos of things by referring to the hypothetical dictionary of a community which communicates by means of images.