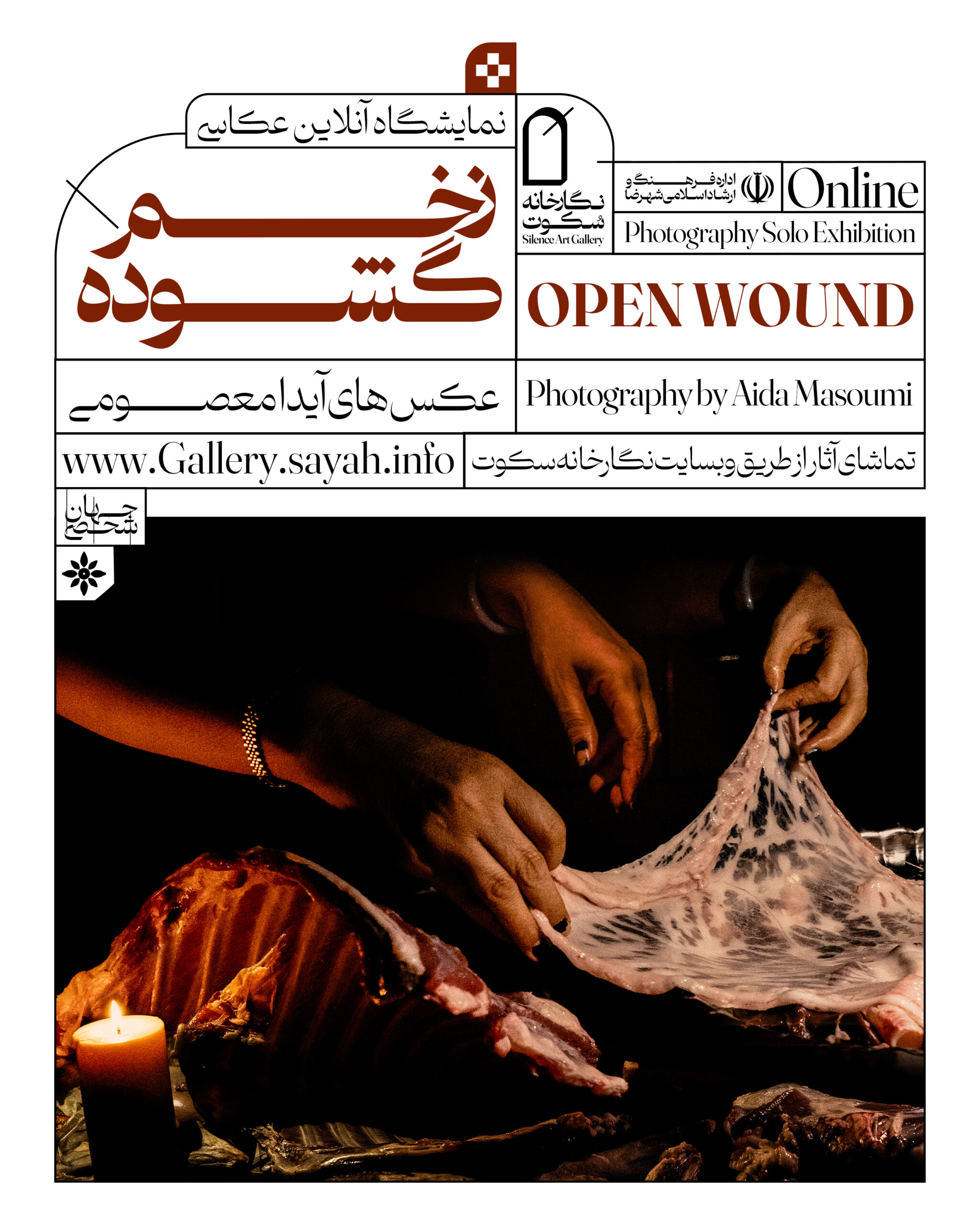

Staged Photography by Aida Masoumi | عکس چیدمان های آیدا معصومی

The image of carcass and meat in the European painting tradition is a vehicle for evoking the relationship between death and beauty. Sliced meat is one of the most disgusting scenes in still life painting, which painters such as Rembrandt have represented as an image of cruelty and violence. Meat in Aida Masoumi's photographs is not a sacred ritual (like sacrificing to a sacred icon) but a representation of the everyday act of cutting and chopping meat, which points to the dichotomy between need and survival in the face of an ancient disgust for the violence of wildlife. In fact, Aida, with an aesthetic gaze, wounds an accepted tradition that, outside of urban life, is placed under an unpleasant element of violence and savagery, so that, despite its acceptance, it is appropriate to the image of the slaughtered and sacrificed body.

| Curated by Aliakbar Sayah |

شمایل لاشه و گوشت در سنت نقاشی اروپایی محملی برای تداعی نسبت میان مرگ و زیبایی است. گوشت تکه شده یکی از منزجر ترین صحنه های نقاشی طبیعت بی جان است که نقاشانی همچون رمبرانت به بازنمایی آن به عنوان تصویری از شقاوت و خشونت پرداخته اند. گوشت در عکس های آیدا معصومی نه به عنوان آئینی مقدس ( همچون قربانی کردن برای شمایل مقدس) بلکه بازنمایی امری روزمره از تکه و خرد کردن گوشت است که به دوگانگی میان نیاز و بقا در مقابل انزجاری کهن از خشونت حیات وحش، اشاره می کند. در حقیقت، آیدا با نگاهِ زیبایی شناسانه، زخمی بر سنتِ پذیرفته شده ای میزند که خارج از زیست شهری در ذیل امری نا خوش آیند از خشونت و توحش جای می گیرد، آنچنان که به رغم پذیرفته بودن آن، با تصویر بدن سلاخی شده و قربانی، مناسبت می یابد.

| کیوریتور: علی اکبرسیاح |

The Promise of Rendering in Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox

| Selected text from Rachel M. Glaser |

The Renaissance period, as an enlightenment period after the strict Christian rules of the Middle Ages, represents a period in which many discoveries have been made for about four centuries and which continues its effects in terms of art as well as political, cultural, and scientific developments. Thanks to the Renaissance, the times when artists could only express themselves through church rules were left behind, and sections from routine life began to appear in the paintings. When it comes to daily life, nutrition is the most essential need of human beings, and since then, foods have begun to appear in pictures, and gastronomic objects, which have intertwined with nature since ancient times, have been frequently used in paintings. Simultaneously, artists have become masters of conveying these gastronomic objects, which they use in their paintings, by giving a message in symbols and allegories. Our study aimed to determine the gastronomic objects in Renaissance painting art and to investigate the philosophical meanings of the symbols and their current reflections by examining them, especially in the context of symbolism.

What then does the ox’s inverted form tell us about this divine reading? It is an accurate representation of how the ox carcass was hung, but it also places the head, in this case symbolic given the decapitation, at the lowest part of the form, positionally beneath the body. Perhaps this is Rembrandt being accurate to his scene, perhaps this is him ribbing at the prioritization of the head in our conception of the body, perhaps it is acknowledging what it means to compare Christ, the Man of all men, to an ox, an animal. Importantly, the head of the ox is hidden in Rembrandt’s version, taking away the surest method of identifying the ox as animal and resulting in a degree of uncertainty. The lack of head means that, without the existence of the title, there is an ambiguity about what the figure represents. This is a very different move from the paintings of van Cleve and van den Hecken which make the carcass exceedingly recognizable as that of an ox. Even though Rembrandt is following many of the conventions of the genre of Flemish slaughtered ox paintings, from the name of the painting to the position of the ox’s form, his choices in rendering the ox and lighting it estrange the Louvre Ox from the already established genre. This painting is about the ox to the point of removing the ox from its assigned position of animal and the painting itself from its assigned position of still-life.